> ENC Master > Climate Encyclopaedia > Upper Atmosphere > more > 2. Ozone > - Cooling

> ENC Master > Climate Encyclopaedia > Upper Atmosphere > more > 2. Ozone > - Cooling

|

|

|

|

Higher AtmosphereRead more |

Stratospheric cooling:Cooling of the stratosphere is favoured by the ozone reduction. But the main cause of stratospheric cooling is the release of carbon dioxide by humen. Therefore, global warming (= tropospheric warming) and stratospheric cooling are parallel effects. Further cooling of the stratosphere may have an impact also on the future development of the ozone layer, because a cold stratosphere is necessary for ozone depletion.

|

|

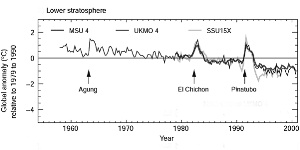

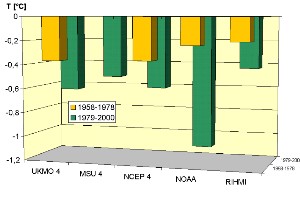

The lower stratosphere seems to be cooling by about 0.5°C per decade. This general trend is interrupted by heavy volcanic eruptions, which lead to a temporary warming of the stratosphere for 1-2 years. Afterwards, temperatures go back to the trend.

|

Why does the stratosphere cool?There are several causes, why the stratosphere could be cooling. The two best understood reasons are: 1) The depletion of stratospheric ozone Cooling due to ozone depletion The first effect is easy to understand. Less ozone means less absorption of solar UV radiation. Less solar energy is transformed into heat in the stratosphere. Cooling by ozone is nothing else than reduced heating by reduced absorption of solar UV-light. Additionally we have to keep in mind, that ozone acts in particular in the lower stratosphere also as greenhouse gas. Cooling in the lower stratosphere is therefore also reduced heating by reduced absorption of infrared light. In about 20 km altitude the UV-light and infrared light effect are nearly equal. But we have not only to take into account the greenhouse effect of ozone, which become less and less the higher we go.

|

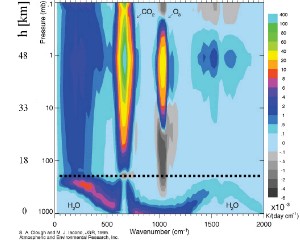

Cooling due to the greenhouse effect Greenhouse gases (CO2, O3, CFC) generally absorb and emit in the infrared heat radiation at a certain wavelength. If this absorption is very strong as the 15µm (= 667 cm-1) absorption band of carbon dioxide (CO2), the greenhouse gas can block most of the outgoing infrared radiation already close to the Earth surface. Nearly no radiation from the surface can, therefore, reach the carbon dioxide residing in the upper troposphere or lower stratosphere. On the other hand, carbon dioxide emits heat radiation to space. In the stratosphere this emission becomes larger than the energy received from below by absorption. In total, carbon dioxide in the lower stratosphere and upper troposphere looses energy to space: It cools these regions of the atmosphere. Other greenhouse gases, such as ozone (as we saw) and chlorofluorocarbons (CFC), have a weaker impact, because their absorption in the troposphere is smaller. They do not entirely block the radiation from the ground in their wavelength regimes and can still absorb energy in the stratosphere and heat this region of the atmosphere.

|

|

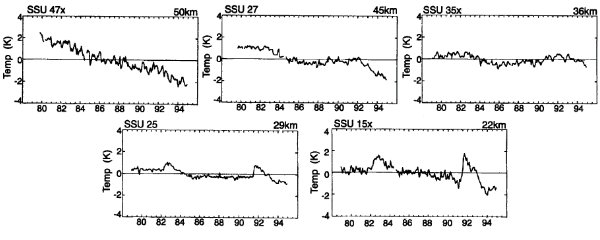

Where does cooling take place?The impact of ozone decrease is more relevant in the lower stratosphere in the region around 20 km of altitude. As you see from Fig. 3 the impact of cooling due to increase of carbon dioxide is high in the upper stratosphere between 40 and 50 km. As we can imagine from this different effects, cooling is not homogeneous over the whole stratosphere. So, the processes have not to be observed only in the lower stratosphere as shown in Fig. 1, but also in other altitudes. The figures below give you an idea.

|

|

|

4. Trends for cooling in the stratosphere in several altitudes

|

|

Other influence Surface warming due to the greenhouse effect might also change the heating of the Arctic stratosphere by changing planetary waves and/or their propagation. These waves are triggered by the surface structure of the northern hemisphere (mountain ranges like the Himalayas, alternation of land and sea) . Conclusion Stratospheric cooling and tropospheric warming are intimately connected, not only through radiative processes, but also through dynamical processes, such as the formation, propagation and absorption of planetary waves. At present not all causes of the observed stratospheric cooling are completely understood. Further research is required.

|

About this page:author: Dr. Elmar Uherek - Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz

|