> ACCENT en > UQ 2 Mar 07 Urban air > R: Kerbside measurements

> ACCENT en > UQ 2 Mar 07 Urban air > R: Kerbside measurements

|

Particle measurments at the kerbsideKatja and Claus continue their conversation. “What about Conny?” Katja asks with some impatience. “Do you think she is living in very unhealthy conditions?” |

Claus hesitates, then he carefully answers: “I do not think that she lives in a very unhealthy environment. Nowadays the exhaust gases in a town are less harmful than in the past. Many severe diseases that were deadly 100 years ago are hardly found anymore. Industrial plants have filters and cars have catalysts. |

|

|

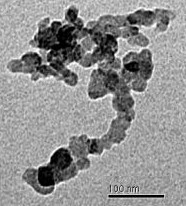

Instead people focus more on the small risks we are continuously exposed to. This includes particles and the soot coming from exhaust pipes of cars, in particular diesel vehicles without soot filters. But also the rubber from tyres abrades on the street and forms little particles. They go into the air and we inhale them. But speaking about this we should never forget: It's much more harmful for example to smoke cigarettes.” 2. Image on the left: This is how diesel particles look like, enlarged by electron microscopy. © K. Park, F. Cao, D. Kittelson, and P. McMurry |

|

Katja shakes. “I would never smoke. ... But how do we know how many dangerous particles there are in the air?” A study has been carried out by colleagues of mine in Manchester in Northern England. There, they installed a measurement platform next to the street which was vertically movable. In this way they could see how many particles there are next to the pavement and how many of them are still present at the height of the third floor of a house.” “Which means where Conny is living ...” Katja adds. |

|

|

|

“Exactly! Here you can see how the instruments have been installed in front of the townhall by a busy road. The platform can be moved up and down. And this is what it looks like if you look from above into the street.” |

|

|

5. View into a street canyon in Manchester. |

|

“And what is the result of the measurements?” Katja asks. “I will show you two series of results for ultrafine particles. These are the smallest particles atmospheric scientists are able to measure. They are much smaller than one thousandth of a millimeter, and much much smaller than the thickness of a hair. |

|

Katja sighs. It's not easy to understand such results. “But if the particles are that tiny are they really dangerous?” |

|

“If particles spread in a street, is it always in this way?” Katja furrows her brows: “Phew, this is complicated.” “Yes,” Claus agrees, “but nevertheless we can learn a lot from such experiments.” |

|

“Hmmm – and the particles from Africa we spoke about ... don't they enter the streets?” “I understand. But that's all a bit messy. And if there are clean cars with catalysts in the town and out of town there is a big and dirty chemical plant releasing particles, which are much more toxic how can we find this out? Or for example in Spain ... if there are many particles in the streets, but most of them come from a sandstorm in Sahara or from forest fires. How can we know?” |

|

“That hits the mark! Exactly this is the problem also for the politicians who make the laws in order to reduce particle emissions. It is still difficult for us to estimate the health danger emanating from particles. Indeed, they can consist of many different compounds. Nowadays there are measurement stations in many towns for air quality control. However, they count only the number of particles of a certain size range. Generally smaller particles are more dangerous than larger ones, but it is not well known what influence the chemical composition of the particles still has. |

|

“Such investigations are unfortunately by far too complicated to be carried out for each city. Therefore we need to assume that in busy streets the pollutants are dominated by the traffic. For most of the days this assumption is reasonable. And we make laws in order to limit the number of fine particles at these locations.” |