|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clouds & Particles

Clouds cover in average about 60% of the Earth. They become most useful for us, if they cause rain. But 90% of all clouds dissolve again, without any rain. Clouds play a very important role in the Earth's energy budget. They can reflect part of the radiation coming from the Sun, so that its heat does not warm the Earth. But they can also absorb heat radiation coming from the Earth and keep the air warm. In this case they behave like a greenhouse gas.

|

|

|

|

|

Encyclopaedia

Link to topic

Clouds & Particles

|

|

|

|

|

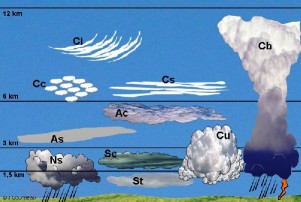

1. The different clouds in the troposphere. St: stratus, Sc: stratocumulus, Nb: nimbostratus; Ac: altocumulus, As: altostratus; Ci: cirrus, Cs: cirrostratus, Cc: cirrocumulus; Cu: cumulus, Cb: cumulonimbus.

Author: J. Gourdeau. Click to enlarge! (75 K).

|

|

|

Cloud types and formation

Apart from stratospheric ice clouds, which are seldom observed and usually only in polar regions, all clouds form in the troposphere between the ground and 15 km of altitude. We give latin names to clouds depending on their shape and altitude. Some cloud types often lead to rain, some others like the higher clouds hardly ever result in rain.

Clouds consist of water droplets or little ice particles if the surrounding air is colder than 0°C. Droplets form during a process, which is called condensation. This takes place if the concentration of water molecules, which are in the air as water vapour, becomes too high. We say, the air is saturated with water and cannot hold any more moisture.

|

Particles / Aerosols

All liquid or solid particles in the air that do not consist of water are called aerosols (matter dissolved in the air).

Such aerosols can consist of dust, which has been risen from the ground. Just think about the big sand storms in the Sahara. Dust is certainly also formed in our towns, for example soot coming from industry and cars. Particles in the clean air over the oceans can consist of sea salt (sea salt aerosol). The spray, caused by the wash of waves, evaporates in the air and the salt particles within it are then floating in the air as aerosols. You notice this effect as far before you reach the shore you can feel the taste of the sea on your lips.

|

|

|

|

|

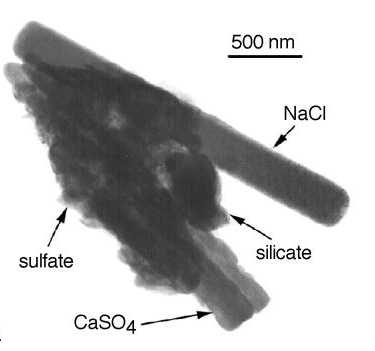

2. Image of mineral dust collected from the marine troposphere. © 1999, The National Academy of Sciences

|

|

Fungi spores, bacteria, pollen, products of biological degradation ... all these can be called aerosols and some of the particles can be 100 µm in size or even bigger. At the other end of the size range aerosols can also consist of a few molecules, so called molecular clusters. Modern particle measurement allows to detect particles down to 3 nm size (i.e. three millionth of a millimetre). Typical candidates are aerosols of sulphuric acid or small organic aerosols just formed by a chemical reaction in the air itself.

Like all other components of the atmosphere, aerosols are not only formed, but are also removed again.

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Transport of aerosols: pollution is swirling above the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of France (bottom left).

Source: NASA. Click to enlarge! (68K)

|

|

|

One possible way of removal is dry deposition, i.e. the process of descent due to gravitation and sticking to surfaces. Another way is via the wash-out of particles when it rains, here they are caught by raindrops and brought back to the ground. Aerosols close to the ground (< 1,5 km) remain from half a day up to two days in the air. With increasing altitude the residence time increases, too. Aerosols, catapulted into the stratosphere during a volcanic eruption, may remain in the atmosphere for 1-2 years. Like clouds, particles also have an influence on the light which passes into the atmosphere on its way to Earth or comes back as heat radiation from the Earth. Particles can reduce the transparency of the atmosphere.

|

The water cycle

Compared to the 1.4 billion km3 of water stored in the oceans, the tiny amount of 12,900 km3 (about 0.001% of the Earth's water resources) in the atmosphere seems to be negligible. However, for the climate system it is important. First, the water in the air is a system in continuous movement. About 500,000 km3 travels every year through the air, evaporates, condenses, and falls down as rain and snow. The atmospheric amount is 40 times exchanged. Secondly, only the water in the atmosphere has a big impact on the light on its way to the Earth's surface or back to space. If the amount of water in the air becomes higher due to global warming and we have more clouds on average, this will have a strong impact on the energy balance of our planet.

|

|

|

|

|

|

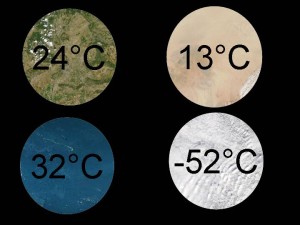

6. Imaginary temperatures if Earth was covered with different surfaces, that have various albedos. The higher the albedo (= fraction of the sunlight reflected), the colder the Earth. Author: J. Gourdeau.

|

|

|

Cloud's impact on the climate system

If clouds are white on top they reflect sunlight like ice and snow. But they can also keep the atmosphere warm like a greenhouse gas due to absorption of heat radiation. Both effects influence the average temperature on Earth, positively or negatively. Our Earth has an average temperature of 15°C. See on the left, what the temperature would be, if the whole Earth was covered by snow, desert, agricultural land and forest or oceans. You can imagine that 10% more clouds, as white as snow, would have a strong influence. However, clouds are not always white and the greenhouse effect of some clouds can outweigh the increased reflection of sunlight (= increased albedo).

|

|

|

|

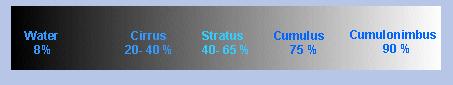

7. Different clouds have different albedos. Author: J. Gourdeau

As we see, clouds have very different properties, which in turn depend on the properties of particles in the atmosphere. This makes it very difficult to foresee what will happen, if global warming leads to a higher concentration of water vapour in the atmosphere and therefore results in the formation of more clouds.

Please have a look at the section CLOUDS & PARTICLES in the Climate Encyclopaedia in order to learn more.

About this page:

Author: Dr. Elmar Uherek - MPI for chemistry, Mainz

English proof reading: Sally Taylor, University of Leeds

last published: 2005-06-14

|

|

|

|